Basque ethnography at a glance

Childbearing and childbirth have always been of considerable interest to family and community members, as shown by the remarkable variety of beliefs shared and gathered about newborns.

Many of them were related to pregnancy. According to a most widespread belief, should the craving of a pregnant woman be not fulfilled, her baby would be born with a birthmark, called antojo, literally ‘craving’, similar in shape to whatever she had craved for but could not satisfy.

The gender of the expected child was another matter of great concern. It was believed that a pointy pregnant belly meant she carried a boy; and the same applied for a protruding navel. Besides, the presence of reddish spots on the face of an expectant mother foretold the birth of a boy; on the contrary, a clean face anticipated a girl.

Some would even look at the moon in order to determine the gender of the future offspring. Women who became pregnant under a waxing moon were said to give birth to boys, whereas girls were supposed to be conceived in a waning moon.

Should parents be asked where babies come from, answers were varied, including the myth that storks deliver them, usually in a cloth bundle, a small box, or a basket dangling from their beak.

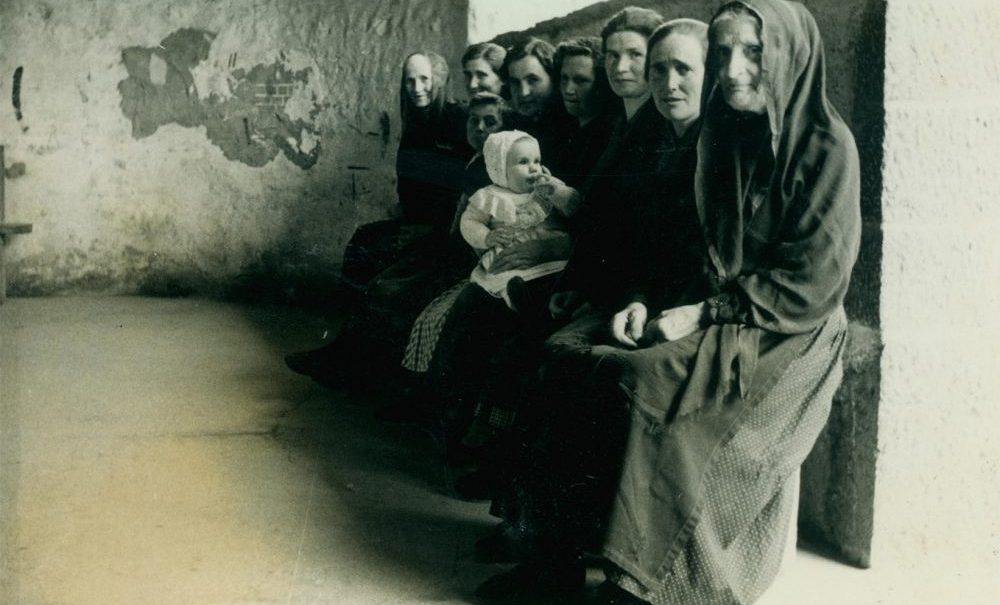

But in older days children believed newborns were brought into the world by midwives. So they were told and so it really was until the 1950s. Women gave birth in their homes with the aid of relatives, neighbours, and a local midwife. Midwives played an important role assisting women in childbirth, and general practitioners were called only if a serious problem arouse. The figure of the midwife as a baby bearer is thus quite understandable.

The mentioned childhood beliefs varied from location to location, even from household to household, all sharing a common purpose: namely, to divert children’s curiosity about procreation. In those days children knew little about sexuality, primarily because their parents would not talk to them about it. Children receive huge amounts of information today, both at home and at school. And also the media are very influential.

Ziortza Artabe Etxebarria – Popular Cultural Heritage Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

(Adapted from Rites from Birth to Marriage, part of the Ethnographic Atlas of the Basque Country collection)