Basque ethnography at a glance

Historically, save for exceptional cases, women have been relegated to the private domain of the household. Their duties included the activation of the symbolic family grave in church, which was in effect conceived as an extension of the house itself.

Nonetheless, there have been a wide range of trades and occupations away from the homestead mostly performed by women, though often considered secondary. To name but a few: midwives, seamstresses, schoolteachers, marketeers, milkmaids…; and among others, particularly in coastal localities, net makers, errand girls at port, fish sellers and clam diggers.

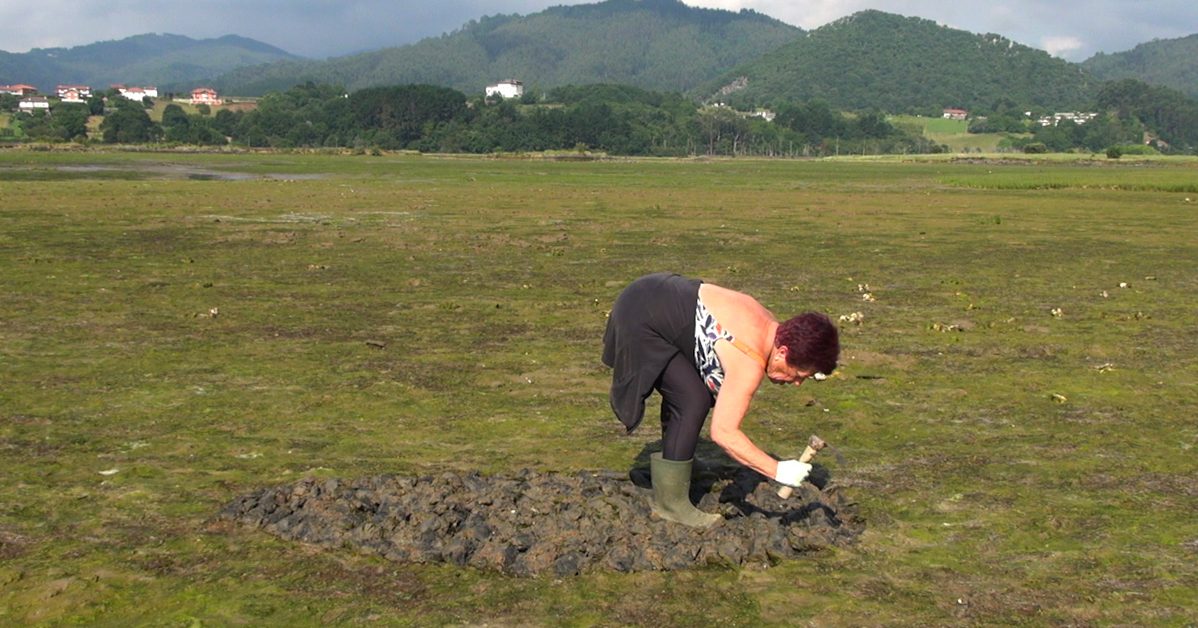

Commissioned by Busturia Council (Bizkaia) in 2018, a video titled Busturiko emakumeak, bizitzaren ardatzean [Busturia women at the heart of life]. We were fortunate to meet with local women from a variety of walks of life and experienced in different jobs, among them Rosa Mari Mintegi, a dedicated clam digger. Here follows a brief description of what clam digging entails.

A group of between 17 to 20 women devote themselves to clam digging in the Urdaibai estuary during low tide hours. The precious clams —the so-called txirlak—, are dug out of the sand by hand from October to February, and often the season lasts right through until March. So they work for six months and rest for another six, being liable to social security contributions for the full year.

All that is required for clam harvesting is a short-handled hoe, or atxurtxua, and a bucket, and of course, a pair of gloves. Two tiny holes in the sand, called begiak, indicate the location of the mollusc. Once located, it is dug up using the edge of the hoe head. Should there be no indication, the only option is to dig around, atxurren egin, looking for them. Further comments are made about the large amounts of sand entering the estuary lately and conditions having only worsened.

Clam fishing is said to be hard work because of the long hours of crouching in an uncomfortable position, but all the same, it can be highly entertaining.

Clams must be 38 mm in length to be harvested. Capture depends on day, tide, moon and weather conditions, and may vary from as little as eight clams to as much as eight kilos, for the sake of an example. Clams are said to be very capricious, not too fond of wind, but keen on dull days —egun ustel-usteltxuak, in her own words—, fine, persistent rain, locally known as txirimiria, and fog.

Initially, they themselves took charge of selling the harvested clams directly to private customers and restaurants in the area. According to subsequent regulations, all clams harvested in the surroundings were to be taken to the premises of the fishers’ guild in Mundaka (Bizkaia) for distribution.

The tricks of the trade have traditionally been transmitted from mothers to daughters, becoming a long-standing tradition for some families.

Akaitze Kamiruaga – Popular Cultural Heritage Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa