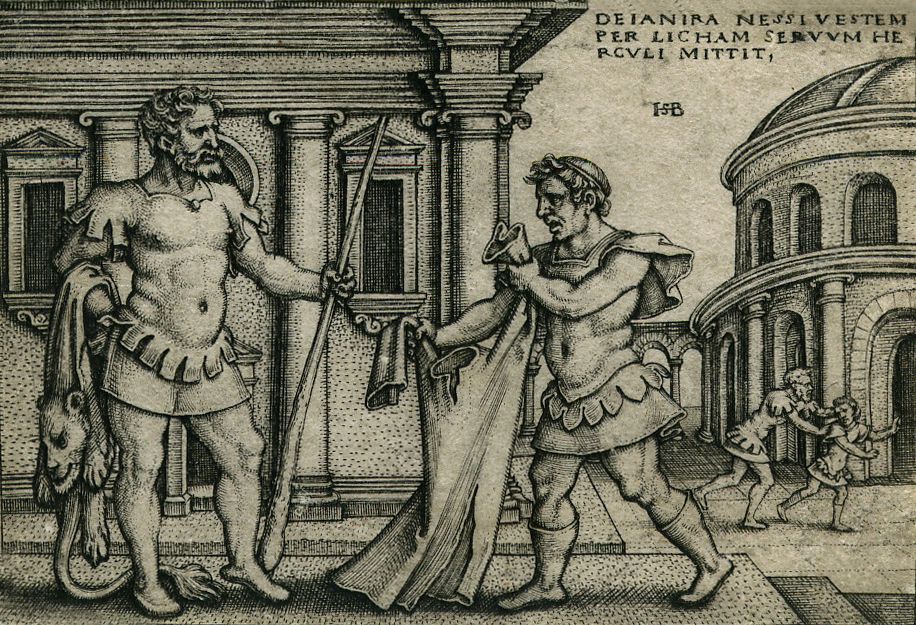

The shirt of Nessus.

Those surprised by the striking parallels between legends of the Basque Country and India should be still more amazed to hear in them echoes of age-old myths such as the shirt of Nessus, Medea’s poisoned dress or Harmonia’s cursed necklace, all of them fabled objects capable of inflicting a most painful death to those who, unconscious of their fatal effect, have the temerity to wear them. A summary of the story of the centaur Nessus by the great French mythographer Pierre Grimal will provide us with a higher basis for comparison:

After his marriage to Deianeira, Heracles lived at Calydon for quite some time; there Deianeira bore a son, Hyllus. Later, husband and wife went into exile, and in their journey, the centaur Nessus tried to rape Deianeira while he ferried her over a river. Heracles shot Nessus, and as he lay dying, Nessus persuaded Deianeira she could compel her husband to love her by giving him a potion made of blood collected from his wound. Heracles and Deianeira were welcomed to Trachis by King Ceyx, and the three of them fought the Dryopes. When Heracles fell in love with Iole, driven by jealousy and willing to revive his love for her, Deianeira dipped a tunic in Nessus’ blood and sent it to Heracles. As the tunic was warmed by his body, the poison which it contained became active and attacked his skin slowly tearing off strips of it. Unable to bear the pain, the hero burnt himself to death on Mount Oeta. On realising the true nature of the so-called love potion, Deianeira committed suicide. Her tomb would be shown at Trachis.

The necklace of Harmonia.

There are numerous lessons to be drawn from our rather quick tour through traditional narrative, but one stands out. Oral legends resemble undocumented migrants who pay little attention to border crossings, languages, social classes or time: they come into the world who knows where or when, land in the least expected corners of the planet, establish themselves within communities that adopt them as their own (yet belong to all), and have the ability to communicate in any language one could possibly imagine. Lo and behold, the tale Dominica Zalbidegoitia from Dima told in Basque, her mother tongue, and Azkue dotted down, is related (kinship varying in degree) to legends retold over thousands of years by so many other people in altogether different languages and beyond continents.

José Manuel Pedrosa – Professor at the University of Alcalá

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Language Department – Labayru Fundazioa

References:

R. M. de Azkue. Euskalerriaren Yakintza. Madrid, 1989.

J. M. de Barandiaran. Eusko Folklore. Materiales y Cuestionarios. Num. XI, 1921.

J. M. Pedrosa. “La contribución de Asturias a la mitología y la leyendística hispánicas: a propósito del cinturón de la xana” in El patrimonio oral de Asturias. Actas del Congreso Internacional. Oviedo, 2016.

Pictures taken from wikipedia.org.

[…] Previous posts by José Manuel Pedrosa: Deadly clothing (I) and Deadly clothing (II). […]