Basque ethnography at a glance

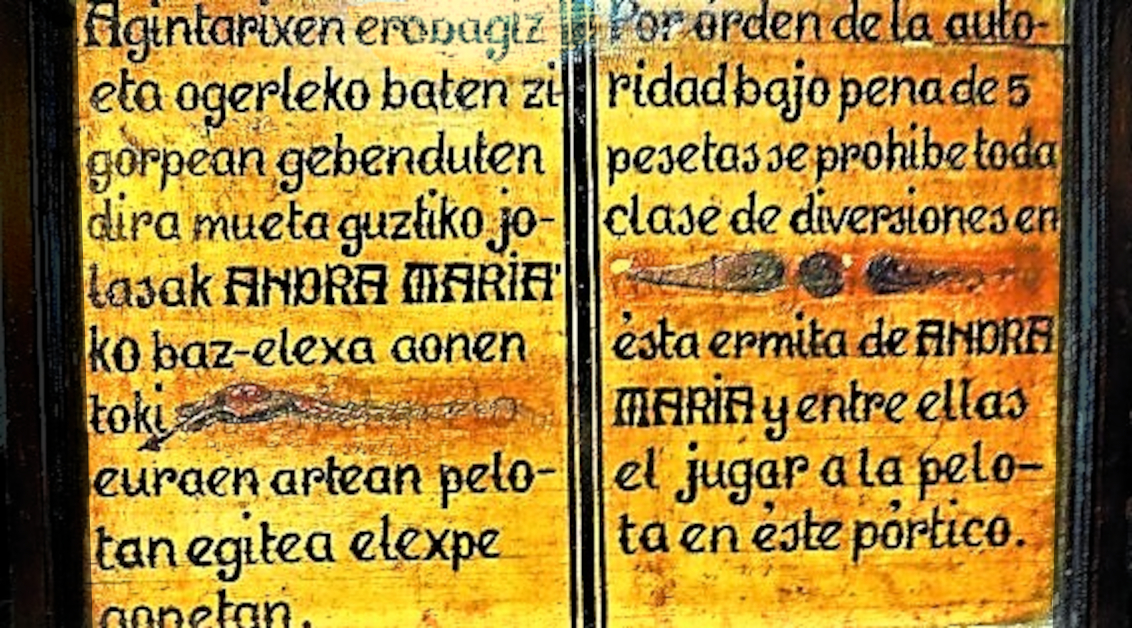

Sign hung in the Chapel of Andra Mari de Ibabe (Aramaio) in 1924. It is currently displayed in the lobby of El Portalón restaurant in Vitoria-Gasteiz.

Basques have our own vigesimal numbering system. It is also used in other Celtic lan-guages, perhaps as a remnant of a proto-Basque language that was widespread though large areas of Europe.

In 1868, the peseta was introduced as the single currency for the whole of Spain, as the result of the decimal metric system coming into force when the Spanish State joined the Latin Monetary Union. The peseta was equivalent to 4 reales de vellón, which were the most commonly used coins up until then; and the 5-peseta coin, ogerlekoa, (popularly known as duro) was therefore equivalent to 20 reales.

As with any currency change, there was an adaptation period until the generational hando-ver, as the people used to the old coins found it hard to get used to the new ones. The real continued to be present as the monetary unit in many cases and the use of 1,000 reales (250 pesetas) as a measurement unit was very common until halfway through the last cen-tury. The ogerleko (from hogeierrealekoa, twenty reales), a new denomination for the du-ro, the 5-peseta coin) then emerged among us. Thus, the ogerleko combined the real de vellón, which had disappeared, with the Basque vigesimal numbering system. In the same way, the 100-peseta note was called hogeiogerleko and that monetary unit was very widely used.

The fact that the currency denomination coincided with the Basque own numbering system meant that the ogerleko would be the usual unit for day-to-day transactions in the first half of the 20th century, particularly in the rural environment and with the older population. Thus, while some people would sporadically refer to the duro in their conversations, the traditional Basque-speaking population always spoke in ogerlekos. It is interesting to note how the expression “I haven’t a duro” meaning being penniless spread in our area and also the surrounding ones, with the representative value of money being given to the duro (the 5-peseta coin) or ogerleko. That importance was perhaps transposed from the Basque to Spanish culture, in which “I haven’t a real” also appeared in a similar way, but the origin in this case was not linked to the Basque system.

In contrast to the above, the laurleko (lauerrealekoa or peseta) did not end up being used, as it did not fit in with our vigesimal numbering system, despite being the fundamental measurement unit. In turn, the ogerleko even became part of our folklore and traditional culture, in songs such as “Mutil txaleko-gorri” included in the Cancionero Popular Vasco by Resurrección María de Azkue:

Mutil txaleko-gorri, zegan dok fanderu hori?

Hamar ogerleko t’erdi, karu dok fanderu hori.

Lad with a red waistcoat, how much is that tambourine?

Ten and a half duros, that tambourine is expensive.

On 31 December 1998, the peseta was replaced by the euro and the relationship between both was not handy (1 euro=166.386 pesetas or, roughly, 6 euros=1000 pesetas) and the Basque vigesimal numbering could not be aligned with the new currency. That made it difficult for many people to express the carrying value of a certain amount of euros and the word ogerleko thus fell into disuse in our vocabulary.

Nevertheless, and as a clear indication of the importance of the concept in our cultural heritage, subsequent coin proposals have emerged, whose use is restricted to some Basque towns and to encourage local consumption, and which have been called ogerleko.

Zuriñe Goitia- Anthropologist