Basque ethnography at a glance

In former days bell ringing guided a farmer’s life. Between earliest sunrise and latest sunset, peals of bells signified the time of day and informed about significant events.

The ringing of church bells at the crack of dawn got the members of the household up and running, particularly those who were to go out to the fields or the woods. At midday bells called for the Angelus prayer. It became customary all over Christian Europe to stop any work and pray on hearing the bell. Let us recall the unforgettable realistic picture by J-F. Millet entitled precisely The Angelus. Until quite recently in the Basque Country, even pelota matches were interrupted on courts at 12 noon to say the Angelus.

The ringing of the Angelus bell at nightfall, known in Basque as abemariak, marked the time to leave either work on the farm or the music and dancing at the village square on Sundays and return home.

The passing of village residents was announced by the tolling of bells or hil-kanpaiak. The death knell communicated the agony and subsequent death to those within hearing range. The manner of ringing the knell depended on whether the person who had died was a child, a man, a woman, a priest or a member of a brotherhood. In some localities special tolling patterns varying the timing, duration and number of strokes signalled the economic status of the deceased. It was an extended practice for those who heard them to momentarily pause in their activities and pray for the soul of the dead parishioner.

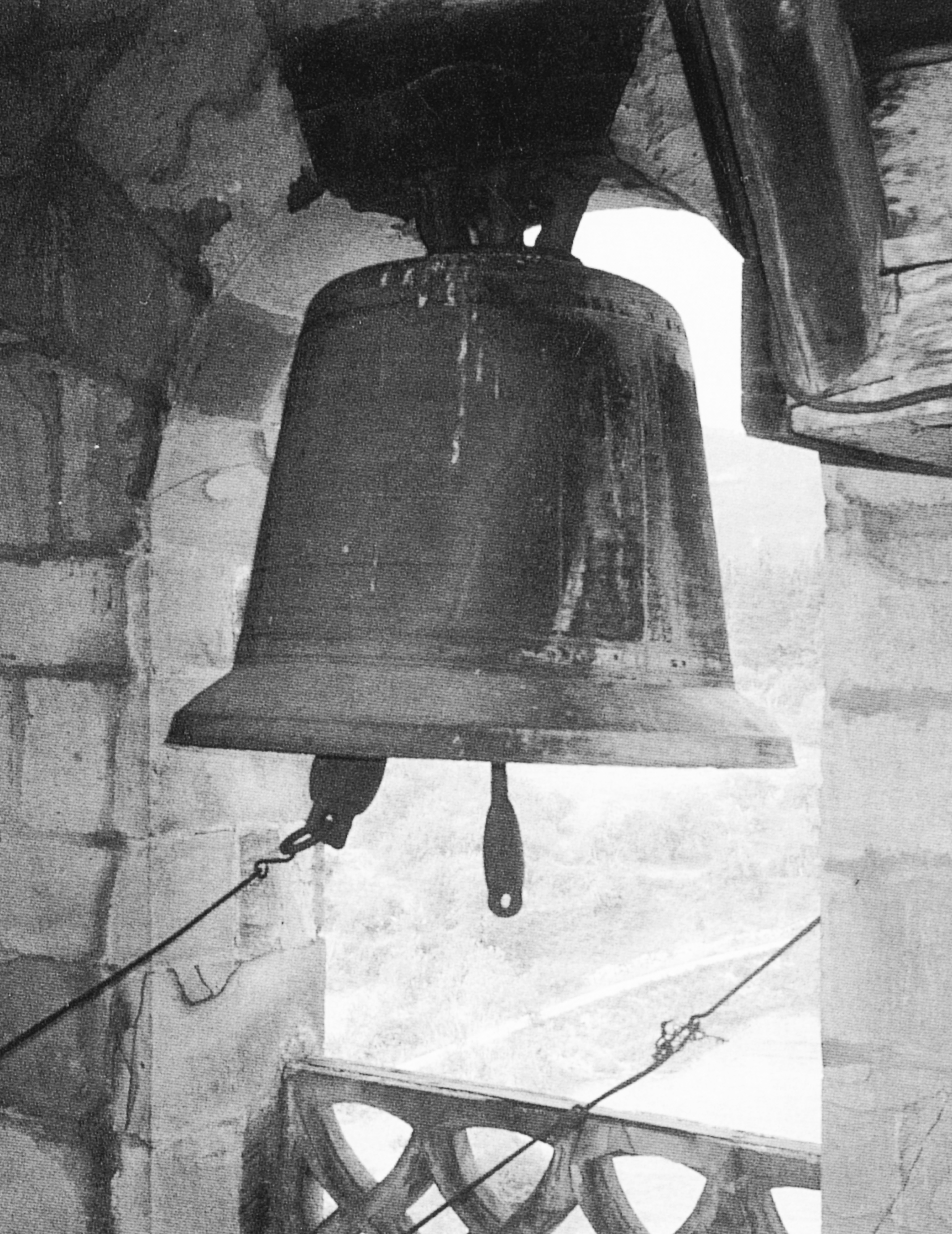

Bells tolled for the dead person throughout the day coinciding with the calls to prayer, and as could not be otherwise, during the transportation of the coffin from the house of the deceased to the church, on arrival of the funeral procession at church and during the transfer of the body to the burial ground. The sacristan was usually in charge of bell-ringing, although in some villages there was a dedicated bell-ringer. In certain places of the Northern Basque Country the woman who cared for the church, named andere serora, could also perform this task. Most church towers had two swinging bells, each with an internal clapper that struck at a steady pace to produce a deep sound. In some neighbourhoods hermitage bells were likewise rung.

The use of bell ringing as a signal device was common: when a house was threatened by fire the ringing of bells called villagers for assistance, during the war bells were sounded to warn of a likely air raid and urged the population to seek cover, etc.

In the old days it was relatively widespread that the priest would speak spells and prayers from the porch of the church in order to ward off weather-related calamities like storms and hail. Ritual formulae were recited while the church bells tolled their sad notes to provide for protection. In some villages such ceremonies, known as tentenublo or tentenube, were conducted starting on the May Cross (3 May) until the September Cross (14 September) to guard fields and houses against the ravages of storms.

Segundo Oar-Arteta – Etniker Bizkaia – Grupos Etniker Euskalerria

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Language Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Reference for further information: Funerary Rites, part of the Ethnographic Atlas of the Basque Country collection.