Basque ethnography at a glance

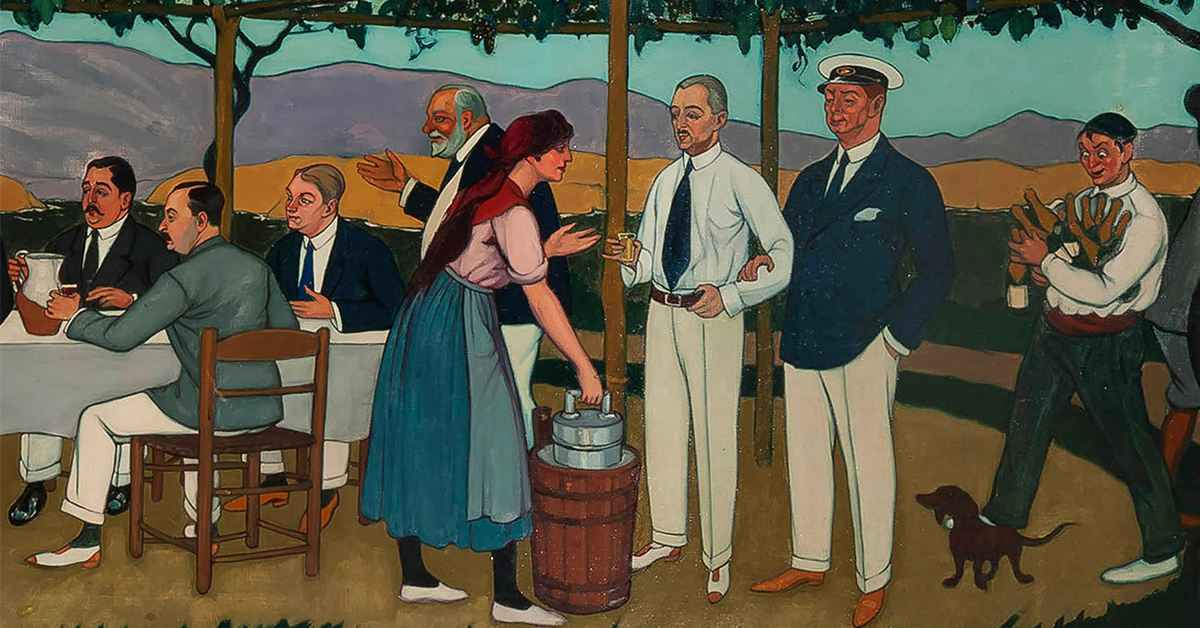

There are times when the smallest detail has much to tell. That is the case of a frieze that José Arrue painted for Bilbao Yacht Club in 1919, which was on the first floor of the Arriaga Theatre at that time. It is now owned by Iberdrola and is kept, along with other works of art, in its iconic Tower.

Well, one of the five fragments of the frieze shows a young girl preparing a lemonade frappe – a typical alcoholic beverage in Basque festivities of the past – to be served to visiting dignitaries. The young girl is depicted with her shirt sleeves rolled up and that is what is remarkable in this particular case.

Indeed, it was unthinkable for anybody to show their bare arms, legs, chest or even hair in public, as it was considered discourteous and reprehensible by the moral standards of society of the early 20th century, standards that were the legacy of previous centuries. That was even more true for a woman, as in our case, as she would have been branded a hussy, brazen and wantonly arousing men. The honour and reputation not only of the woman but also of the whole family depended on her behaviour and, particularly, her public persona.

The case of our young girl is therefore remarkable as her upper limbs are bare. A quick look at the 136 figures on the frieze shows that all of their forearms and wrists are covered by sleeves, except for a cyclist speeding along and the young girl making churn lemonade, as it was known. Therefore, something remarkable.

That was all down to – and that is where the interest lies – the ritual, the traditional way of doing things, around the preparation of that delicious churn lemonade. Thus, the person making the beverage had to roll up their sleeves, something, as can be seen, considered to prevail over other social standards.

Emiliano Arriaga put it perfectly in his Lexicón bilbaíno, written two decades before Arrue painted his work in 1896. He said the following about making churn lemonade: ’The task of turning the recipient immersed in ice in a keg used to be entrusted to the most deadpan person among the diners. They usually sit at the table in shirtsleeves waiting for the lemonade to be served. That is why it is usual to call out “you look as if you are about to have lemonade!” when one comes across someone dressed in that way.’

Churn lemonade was, to quote the same author, ‘…an iced sangria, extremely pleasant on the pallet, served at large and boisterous lunches or summer gatherings known as lemonade parties. The classic version was made out of white chacoli wine, water, sugar cubes and lemon rind’.

To go into further detail, churn was the name of the large bucket which the girl worked and in which she put ice with salt and, placed inside, a metal cylinder with the drink. She would turn the cylinder steadily until the mixture was slushy. We also know that the ice used traditionally came from large cavities in the mountains known as ice pits. The ice was stored there in winter to be sold at the summer festivities, which was a lucrative business in the 18th and 19th centuries.

By the time that the girl painted by Arrue served the delicious elixir to those dignitaries, ice was already produced artificially at the first ice-factory in Calle Ollerías in Bilbao, which opened in 1880. Its appearance led to ice dropping in price, the spread of churn lemonade and the mountain ice pits falling into disuse.

Those new times also saw the gradually disappearance of the headscarves that our grandmothers had to use to cover their hair. And the full-length stockings and collars buttoned right up. In the end, they could begin to show their arms without having to be making churn lemonade. And that was called modernity and freedom.

Felix Mugurutza